The Ontario-born ‘Vogue’ writer’s first book ‘The Power of Style: How fashion and Beauty Are Being Used To Reclaim Cultures’ is out April 27.

“I never thought I would write a book,” says Christian Allaire endearingly. Allaire, whose recognition has grown since joining the U.S. Vogue team as a writer in 2019 — where he lends a particular expertise in highlighting Indigenous fashion creatives — admits he’s not used to being on the other side of the interview. But he’ll have to get used to it, especially after today’s release of The Power of Style: How fashion and Beauty Are Being Used To Reclaim Cultures, his approachable, heartfelt and informative exploration of style.

The name of Allaire’s book comes from a very personal place, and he hopes it will resonate with fashion fans who, like himself, grew up not seeing themselves — or seeing caricaturized versions of their community — represented in the style world. Allaire grew up in Nippissing, Ont. on a First Nations reserve, and initially came to understand the dynamics of dressing via his Ojibwe roots.

“I always loved fashion growing up,” he says, adding that while he consumed all manner of style-focused media in his youth, his appreciation for design and what it communicates was largely piqued from a more familiar source.

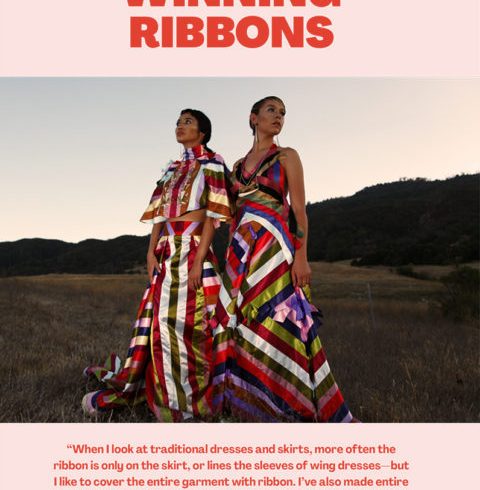

“What got me into it was seeing our traditional wear,” Allaire says of examples like watching his sister, a jingle dancer, dress for powwows; his mother and aunts are also avid sewers, and his late grandmother made him a ribbon shirt when he was young. This item holds special significance in his ancestral community, and in his book, Allaire details the process of making it and the pride in having a new ribbon shirt made as an adult.

“I grew up around [these] beautiful garments, and it shaped my love for them,” he acknowledges, going on to say that the Ojibwe tradition of beadwork, often featuring bold floral motifs, also drew him to a love of colour. “But it’s about more than a love of pretty things,” he adds. “It’s an appreciation of craft. A jingle dress can take months to make. So, I appreciate the thought and time that goes into a design.”

Allaire says that despite his passion for Indigenous design and commitment to covering culturally significant style from around the world, both in his magazine and now book writing, as a teen he actually rebelled against wearing such attire.

“That’s why I wanted to do this book for a younger audience,” he says of The Power of Style. (But don’t be fooled by this notion — everyone will learn so much from these thoughtful pages, regardless of age or where they sit in terms of style knowledge.) “[They’re] so susceptible to wanting to fit in. I went through that myself; wearing a ribbon shirt was the last thing I wanted to do. But I wanted to show that [pieces like that] are special to you, and that’s why you should wear them. Nobody else can wear them or carry on these traditions like you can.”

He also notes that it was intentional to include inspiring creatives such as writer and editor Modupe Oloruntoba, designer Bethany Yellowtail, Cree dancer James Jones, cosplayer Surely Shirley, and fashion entrepreneur Melanie Elturk in The Power of Style. Their voices will especially resonate with a generation that is finally starting to see themselves reflected in the fashion world, primarily because of social media and the visibility it affords.

“It’s been a game-changer,” Allaire says. “I mostly found the people in the book through Instagram.” He also notes that many of his Vogue subjects are sleuthed out via social media, and that virtual platforms have given makers, particularly those not based in major city centres, the ability to reach consumers and fans far and wide. And he says that this has directly affected the fact that now, “it’s easier to find people who are embracing their cultural fashion” and in turn, amplifying these ideas and aesthetics.

Likewise, Allaire opened up the scope of his own book after being approached three years ago to write it. “I initially thought it would be more just about Indigenous fashion,” he says of when Annick Press reached out to him while he was a freelancer. “The more I got into my research, I thought I should open it up to all cultures because it’s not only my culture that isn’t getting covered [by the media]. There are so many cultures that are being ignored in the mainstream. I feel like it’s a much better book as a result.”

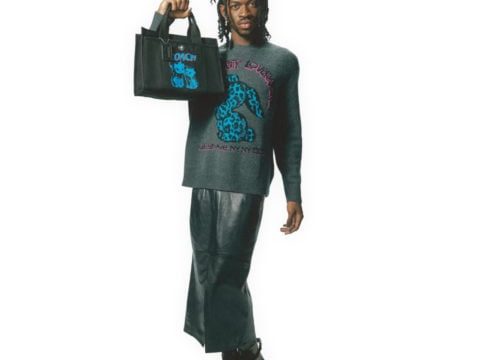

One can’t argue with this given the impressive and delightful scope of those featured in the book, from Jamie Okuma — whose bold designs are featured on the cover as well as inside — to shoemaker Alim Latif, makeup artist Jennifer Bear Medicine, and designers Henry Bae and Shaobo Han. Allaire also draws attention to Billy Porter for his zesty, boundary-pushing ensembles.

“There’s no one doing it like him on the red carpet,” Allaire says. “Every look has a narrative behind it [and] that’s usually not the case with celebrities. He works on custom looks with designers, using a specific reference or with a story to convey. He’s using fashion as art, which is how it should be. You have the privilege to dress up for fun; why not speak to a bigger moment?”

Allaire recalls his own moment when he felt called to do the same. As a fashion journalism student at Ryerson University, he became exposed to Indigenous fashion designers and tastemakers who were incorporating both traditional and contemporary ideas into their work. One example is Justine Woods — Allaire wore a bespoke suit with beadwork detailing by the designer to the 2019 Canadian Arts and fashion Awards ceremony.

“I thought, I need to cover this,” he recalls about the talent he was observing. “No one else was. And I didn’t think of it as disruption; I was just interested in it. Coming from a small town, I didn’t know it was a thing. I wouldn’t see Indigenous fashion — I thought of it more as cultural and for special ceremonies. I didn’t think it could be part of the same conversation.”

Such dialogue is louder than ever these days, and Allaire is optimistic about where it’s heading. “In the past year, diversity and inclusivity have been what fashion’s talking about,” he says. “It may sometimes seem performative and it often is, but at least it’s on people’s minds. A lot of brands that weren’t on people’s radars are being researched and considered. That’s a positive thing. And there’s no going back.”

Speaking of going back, Allaire recently returned to New York from an extended stay in Canada, and says he’s looking forward to turning it out sartorially in days to come. “I’m seeing people wanting to get dressed again, and I’m excited,” he says. Pieces from the Nigerian brand Orange Culture, a necklace from Indigenous designer Warren Steven Scott, and custom-made trousers from Juliette Johnstone are currently on his shopping list. All unsurprising choices given Allaire’s preference for the bright, bold and significant. “What you wear can be more than a fashion statement,” he notes. “It can have a much deeper meaning than it looks, and I think the best fashion does that.”